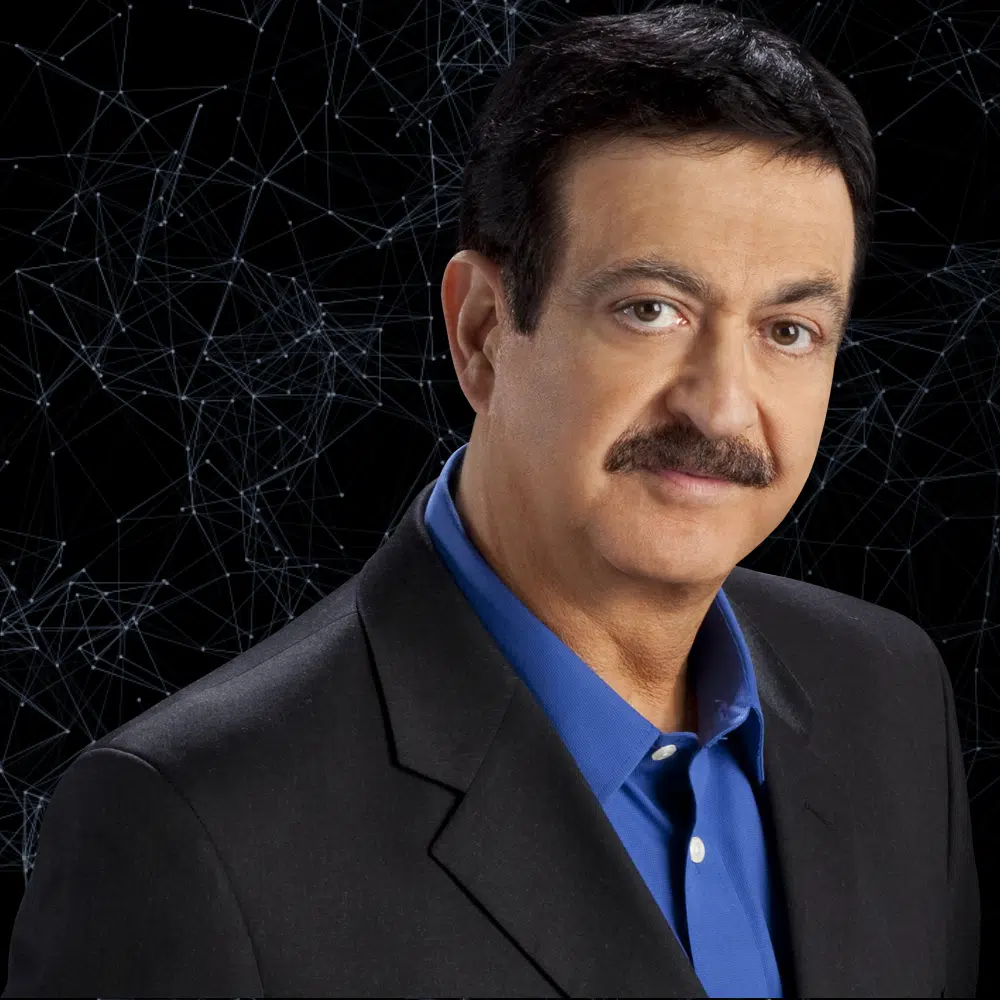

Todd Thompson

MAHNOMEN, Minn. (Minnesota Reformer) – The day after Minnesota officially legalized recreational marijuana in August 2023, agents with the Paul Bunyan Drug Task Force raided a squat, single story cinderblock building across the railroad tracks from a grain elevator in Mahnomen.

The search of the Asema Tobacco & Pipe Shop yielded approximately 7.5 pounds of marijuana, much of it stored in plain sight in mason jars bearing labels like “Black Plague” and “Ghost Candy.” Investigators also seized just under a pound of marijuana wax and, from the till and several people who were present, $2,748 in cash.

Eight months later, Todd Jeremy Thompson, Asema’s owner, was charged by the Mahnomen County Attorney with one count of felony first-degree possession of marijuana.

For Thompson, a blunt talking, occasionally profane 56-year-old enrolled member of the White Earth Band of Ojibwe, neither the raid nor the criminal case came as a surprise.

“I was told by certain individuals that they were going to come. Two different sources,” Thompson told the Reformer during a pair of wide-ranging interviews at what he refers to as his “old school head shop.”

Still, those warnings did not dissuade Thompson from exercising what he believes are his rights under treaty law, applicable federal precedent, Minnesota’s 2023 cannabis legalization law, and the constitution of the Minnesota Chippewa Tribe.

Thompson has a long history of successfully asserting his rights as a Native in the face of an array of legal authorities, but this constitutional clash is not without risk: He could face up to five years in prison and a $10,000 fine.

In the more than two years that have passed since the raid, the retail sale of marijuana has exploded across Minnesota, first with a proliferation of tribally-owned dispensaries located on reservations, and more recently, with a slew of tribal and non-tribal outlets opening off-reservation.

At White Earth, Thompson explained as he gave a driving tour of Mahnomen, the band got a head start in the burgeoning industry because it already had a functional medical marijuana operation up and running.

Rolling down the road, it’s hard to miss that enterprise, which is every bit as aromatic as you would guess. The growhouse is located in a 40,000-square-foot former potato chip factory, now encircled with tall fences and concertina wire. The tribally run dispensary, Waabigwan Mashkiki, is close too, just across the street from the Shooting Star Casino.

As his court case drags on, Thompson has continued to operate Asema, where products on display include bulk tobacco, incense, posters, and a wide array of paraphernalia: glassware, vapes, stash containers, cheap cigars, wraps, vape juice, scales and the like.

Competition from the tribal dispensary has cut into his glassware sales, said Thompson. He’s still making enough to pay his bills, he said, adding ruefully that he probably won’t be in the market for a new truck any time soon.

Comments