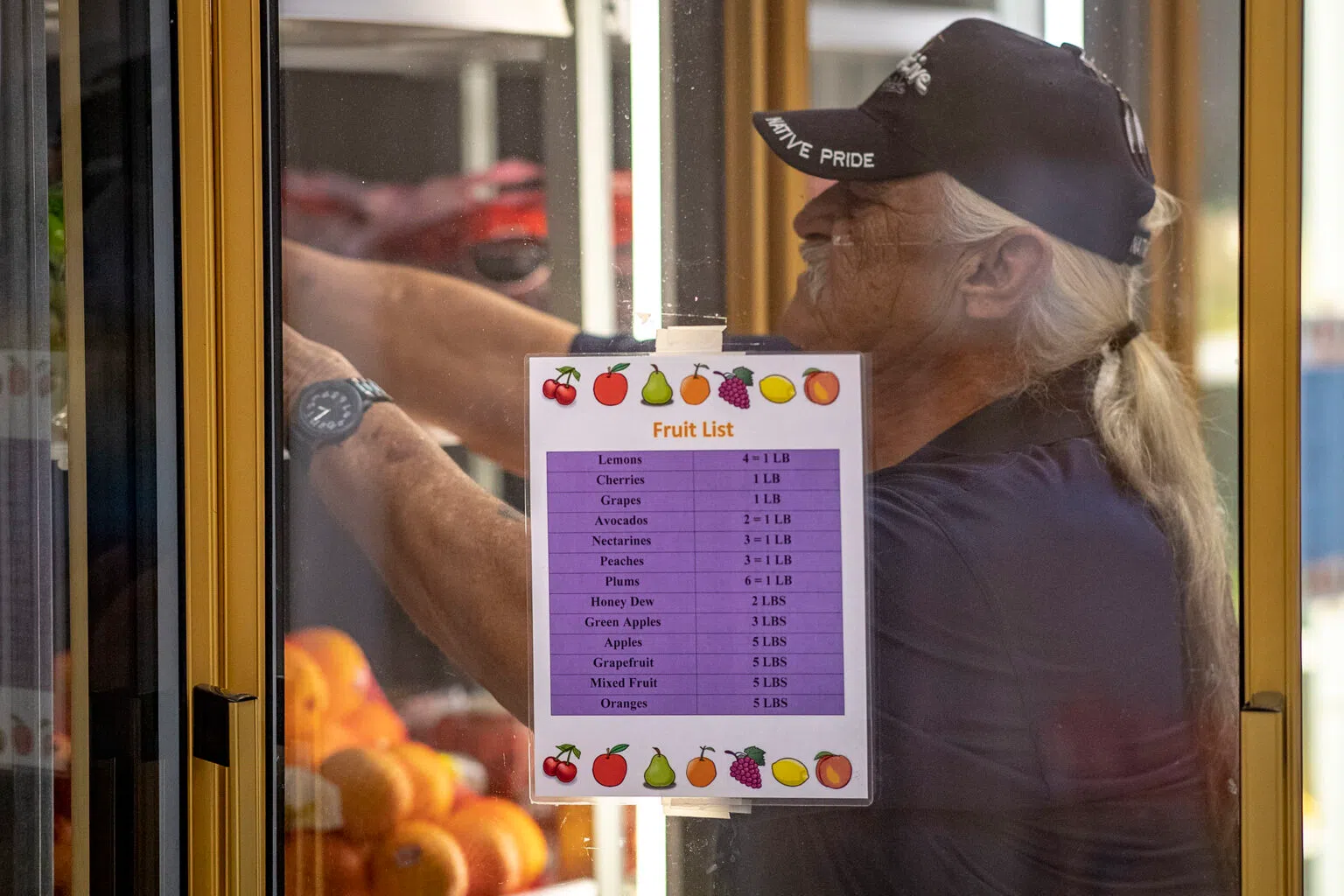

Warehouse worker Robert Paschal stocks a cooler with fresh produce at the Food Distribution Program at Seminole Nation of Oklahoma, Nov. 6, 2018. (Photo by Preston Keres/U.S. Department of Agriculture)

WASHINGTON (North Dakota Monitor)— U.S. Secretary of Agriculture Tom Vilsack apologized to tribal communities this week for delays in shipments and delivery of expired food during a tense congressional hearing that highlighted widespread failures within the Food Distribution Program on Indian Reservations.

Vilsack’s comments followed detailed testimony from leaders of the Chickasaw Nation, Red Lake Band of Chippewa Indians and Spirit Lake Sioux Nation about the food shortages during a rare joint hearing of the House Appropriations and Agriculture committees.

“This is a dire issue that’s evoked a genuine bipartisan and bicameral concern in Congress,” said House Appropriations Chairman Tom Cole, who is a member of the Chickasaw Nation of Oklahoma.

The USDA, he said, had failed in its duty to provide “critical food assistance for tribal members and vulnerable senior citizens” for months, amounting to “gross negligence.”

“Missed and delayed deliveries, empty shelves and bare warehouses have become commonplace,” Cole said.

House Appropriations ranking member Rosa DeLauro, a Connecticut Democrat, said the food shortage was unacceptable.

“It must be among our government’s highest priorities that the most vulnerable communities among us do not suffer from hunger,” she said. “But this disruption to food deliveries has risked exactly that.”

The Food Distribution Program on Indian Reservations provides food to “income-eligible households living on Indian reservations, and to American Indian households residing in approved areas near reservations and in Oklahoma,” according to a USDA fact sheet.

The USDA buys and ships food selected from a pre-approved list to state agencies and Indian Tribal Organizations, which in turn store and distribute the food to eligible participants.

Tribal representatives speak out

The three tribal representatives detailed how those bare shelves have affected their communities and how the USDA told tribes — rather than consulting with them — about a major change in the program’s contract, leading to distrust and anger.

The three also pressed Congress for much more control over their food supply during the four-hour hearing.

Darrell G. Seki Sr., chairman of the Red Lake Band of Chippewa Indians in Minnesota, said his community’s ability to feed people through the FDPIR program was “jeopardized” by failures that have persisted throughout the summer.

“We need more consultation with tribes,” Seki said. “We are the first Americans here. We should be the priority because of the treaties that were adopted under the U.S. Constitution.”

Seki called on lawmakers to “do the right thing” numerous times during the hearing.

Mary Greene-Trottier, president of the National Association of Food Distribution Programs on Indian Reservations and a member of the Spirit Lake Sioux Nation in North Dakota, said the program is essential for tribal communities that exist in food deserts.

The Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program, previously known as food stamps, doesn’t work in some tribal communities, making FDPIR a “critical stopgap,” she said.

“SNAP is an important tool in the feeding program toolbox, but is not meaningful if you lack access to a full-service grocery store or even a convenience store,” Greene-Trottier testified.

She told the committees the Food Distribution Program on Indian Reservations serves about 55,000 people in Native communities each month.

Greene-Trottier also said the problems that began this spring have led to a lack of trust in USDA throughout her community.

Self-determination project

Marty Wafford, under secretary of support and programs for the Chickasaw Nation Department of Health in Oklahoma, said there is an “urgent need for Congress to expand tribal self-governance.”

She testified that a self-determination demonstration pilot program Congress authorized in 2018, which allows some tribal communities to produce and supply more food, has been “highly successful.”

“This inventory and warehousing crisis is an example of how the locally procured food system works,” Wafford said. “We have not experienced ordering or delivery issues with foods secured with the self-determination project, in which we currently supply a variety of beef, pecans and dried hominy.”

For years, she said, tribal nations have been striving to reestablish food production, including growing crops, raising buffalo and cattle and establishing meat processing facilities and fish and shellfish hatcheries.

Tribal representatives testified that instead of consulting them on the change in contracting — that shifted from two suppliers to just one — USDA officials merely informed them in February and then didn’t take their concerns seriously.

Tribal communities were told they wouldn’t be allowed to order any food through the FDPIR program during the month of April, after which the delays, missing shipments and delivery of expired food began.

The USDA has put in place stopgap measures and short-term solutions, but tribal officials told members of Congress that those didn’t fully alleviate the situation, which they said continues to this day.

Tribal leaders called on Congress to make several changes to food procurement, including a regional sourcing model for food distribution.

They told lawmakers the FDPIR program needs a tracking system, so tribal members can see when their food orders have been shipped, instead of being forced to repeatedly call in and hope someone answers the phone.

Review of contracts required

Vilsack told lawmakers, and the tribal representatives who stayed in the room to hear his explanations for the food shortages, that USDA is “committed” to listening to tribal leaders more and keeping Congress better informed of problems with the food distribution program.

He explained that in 2022, USDA began the process of reviewing the contracts for the Food Distribution Program on Indian Reservations, in part because under the federal procurement law, the department wasn’t allowed any additional extensions of the previous contracts.

Following months of meetings and requesting bids from contractors, the USDA received eight proposals in 2023. One wasn’t close to meeting the requirements, leaving a panel with seven to review between September and December.

That group ultimately determined only one application, from Paris Brothers in Kansas City, Mo., met the full list of requirements. That company had been one of the two that USDA contracted with to provide food under the FDPIR program for years.

Paris Brothers told the USDA at the time they had the capacity to handle the full contract, which Vilsack said later turned out not to be the case. The contract costs $35 million per year for the five-year term, totaling $175 million.

Once USDA realized there were mounting problems with the new single-supplier model, Vilsack said staff began working to implement fixes, both at Paris Brothers and for the tribal communities.

For example, the company increased work to seven days a week, boosted the number of shifts per day, hired more temporary and permanent workers and increased training.

The USDA has also signed a $25 million six-month contract with another company to help alleviate the shortage of food deliveries to tribal communities.

Given Paris Brothers’ long record, Vilsack said officials at USDA assumed the issues could be worked out.

But, he said, changes the USDA instituted in August should have taken place sooner and that lower-level staff at the department should have brought the problems to his attention months before he was informed in late July.

‘Make sure nothing like this ever happens again’

Members of Congress on the two committees said they still have concerns over Paris Brothers and the USDA’s management of the program.

“It’s critical that this crisis is resolved quickly and the changes are made in the contracting process to make sure nothing like this ever happens again,” Cole said.

House Agriculture Appropriations Subcommittee Chairman Andy Harris, a Maryland Republican, said he expects the USDA to fire at least one person for not addressing the problems at Paris Brothers sooner and that the department needs to levy fines against the company.

“If somebody’s head doesn’t roll over this, the American taxpayer should be furious,” Harris said. “This is tens of millions of dollars, and I’m not even talking about what we did to our tribal nations — delivering outdated food, missing shipments.”

When the Appropriations panel next meets with USDA officials, Harris said, he expects witnesses to arrive with detailed information about what fines were levied against Paris Brothers and how much the federal government had to spend to ensure food delivery to tribal communities.

Harris expressed “no confidence” Paris Brothers would be able to reestablish on-time, unexpired food deliveries to tribal communities and questioned whether the company was fulfilling other contracts ahead of tribal communities.

“I suspect that they shorted the tribal nations while keeping other commercial contracts whole. And we should never tolerate that,” Harris said.

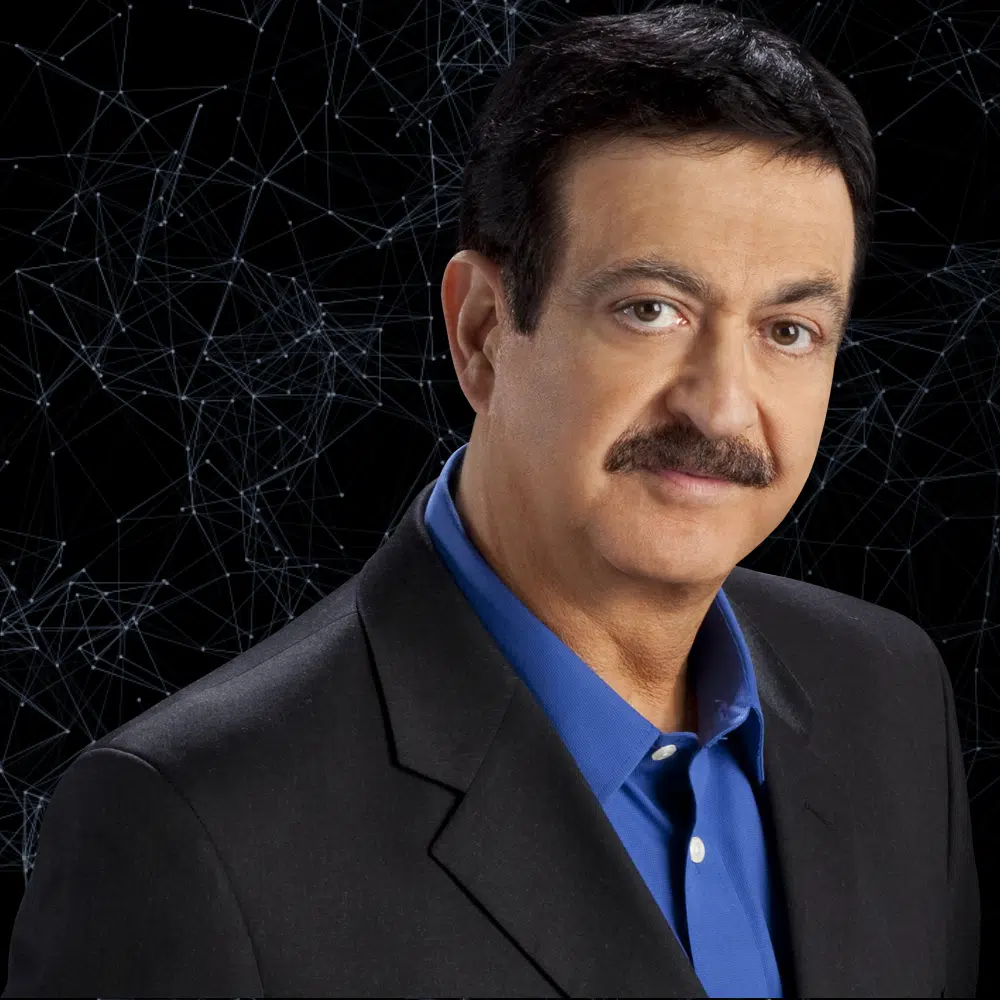

Georgia Rep. Sanford Bishop, Jr., the ranking member on the Agriculture Appropriations Subcommittee, said it was a “shock” to hear of the problems within the FDPIR program after years of it being well run.

Bishop pressed for more funding for the Agricultural Marketing Service, the office within the USDA that handles contracting.

The last full-year government spending bill, which Congress approved earlier this year, provided 12% less in funding for the service than was requested, he said. That represented a $14.8 million cut to its enacted funding level.

“Congress cannot meet 21st-century needs and challenges with 20th-century budgets,” Bishop said.

Georgia Rep. David Scott, the top Democrat on the Agriculture Committee, said lawmakers must bring representatives from Paris Brothers in front of Congress to answer questions about the mismanagement.

Paris Brothers declined to comment in response to a request from States Newsroom, writing that “due to our ongoing work with USDA on this matter we are deferring all inquiries to the USDA communications team.”

Comments